My mother and all my aunts and all their friends used to play the piano. Nobody was brilliant at it; but they all did it. Many (but not all) girls of my generation learned to play too. I was so possessive of our piano that I carved my name into the back of it. Teaching girls to play the piano is less common now, not such a matter of routine. Times have changed.

Monday, September 13, 2010

My Piano and I

My mother and all my aunts and all their friends used to play the piano. Nobody was brilliant at it; but they all did it. Many (but not all) girls of my generation learned to play too. I was so possessive of our piano that I carved my name into the back of it. Teaching girls to play the piano is less common now, not such a matter of routine. Times have changed.

Saturday, July 31, 2010

The Piano Lurched

Contact was sharp…

I jolted from immediacy of senses torn from mind:

Such was I at unawares with you –

To strike with Master’s single chord that pounced and caught me blind –

Piano, how you lurched and rent me through!

Delightful music welcomed me to drift in quasi-syncope:

Soft tranquillo sought to rest my bones –

I glided reaching largo; sang with sweet cantabile, and

Forte let me in to louder tones.

I cried with lacrimoso; squirmed when agitato flared;

My hearing rang when fingers danced the trill.

And so it was, this maestro grand was genius declared –

Acting out in music for the thrill.

Translating pen to piano, this player takes me back thro’ time…

In the chamber, fine composers charm:

I watch the manic hands of Liszt abound with tunes sublime;

Mozart teased my mood with stark alarm.

Then entered Bach to demonstrate his mathematic flare,

Calculating notes supreme of form.

And I – the minion audience – sat wanting in my chair,

Having heard my idols all perform.

Did Darwin’s theory tell at all why Man evolved this way?

Why would music help him to survive?

But scientific muse had veered my thoughts from this display, and

Music called: ‘Just listen - you’re alive! ’

The maestro draws conclusion; lets the piano die a death

To stand as wood, inert just as before –

A pollished casket lined with keys, at calm from naught of breath,

Bade me scream: ‘Bravo! ’ and ‘Hail! Encore! ’

He wakes the box to dance again with noble works of art:

Resurrected; fully primed with zest.

Now even I was back to life with reason in my heart –

Heightened from the pounding in my chest.

| http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/the-piano-lurched/ |

Sunday, June 6, 2010

Franz Joseph Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn is best remembered for his symphonic music, honored by music historians who have dubbed him the "Father of the Symphony." That is a well-known fact. But did you know that Haydn worked his way from peasant to Kapellmeister where he lived in the house of a prince? Did you know that although Austria was his home, he traveled to London to write his most famous symphonies? Did you know that Haydn's oratorio "The Creation" grew out of his love of nature, as he was an avid hunter and fisherman? Or did you know that Haydn was mentor to a young music student by the name of Mozart?

These are the lesser-known facts, the parts of Haydn's life that allow us to peek inside a great man's legacy to see what made him tick. Haydn was indeed a self-made man. Born in the small village of Rohrau, Austria on March 31, 1732, Franz Joseph Haydn was the second of twelve children. His father was a wagon maker by trade, but quite musical. On Sundays, the Haydn family often gave private concerts. Haydn's father played the harp while Haydn and his mother sang. A cousin who was a schoolmaster recognized the five-year-old boy's talent and offered to take him into his school so that he could receive musical instruction. The food portions for the children were meager and Haydn himself said that "there was more flogging than food." Still, Haydn persevered, determined even as a young boy to maximize the opportunity and learn all that he could.

At the age of eight, Franz Joseph Haydn became a choirboy for the Viennese Cathedral. Again, the food was far less than what a growing youth needed and the choir children's treatment in general was harsh. Haydn stayed, learning all that he could about church music, until puberty changed the timbre of his voice and he was cast into the streets of Vienna with nothing more than a change of clothes. At the age of seventeen, Haydn found lodging and work. He gave music lessons and played in the serenades to earn money. An open door presented itself in the form of an Italian composer named Niccolo Porpora who hired Haydn as his accompanist. Haydn's status was that of a servant, but Porpora did adequately feed him - something he had not enjoyed at the school or the Cathedral - and taught him Italian, voice, and composition. Again, a positive-minded Haydn saw it as an opportunity.

With practice and performance, Haydn's musical prowess and fame grew with time. He was offered the position of Music Director for Count Morzin. From there, Haydn accepted employment with the Prince Paul Anton Esterhazy where he became the Vice-Kapellmeister and later Kapellmeister. His duties were intense, ranging from the administrative responsibilities associated with monitoring the needs of the musicians under him to himself composing music for orchestral, operatic, and chamber music performances. His response to the challenge was as it had always been - Haydn exhibited not only the stamina for that which was required of him, but the brilliance of creation that made his music famous. While in the employ of the Prince, Haydn composed eleven operas, sixty symphonies, five masses, thirty sonatas, one concerto, and hundreds of shorter pieces.

Haydn's positive attitude and sense of humor made him a favorite among musicians. Music students valued his knowledge and skill and considered it an honor to learn from him. One such musician was Mozart. Although Mozart was much younger than Haydn, the two men treated each other with a mutual respect reserved for the obviously gifted. Although Haydn openly opined Mozart as the more dramatic composer, his young counterpart looked to Papa Haydn as a mentor and the master of quartets.

Haydn's sense of humor often came into play during his thirty-year tenure with Prince Esterhazy. The prince had become complacent when listening to Haydn's symphonies, even falling asleep at the performances. This was something that seared the feelings of the diligent composer, especially when the prince emitted a loud snore during a part of the symphony over which Haydn had especially labored. Haydn decided to create a new symphony for the prince, a symphony that he hoped would "get Prince Esterhazy's attention." This particular symphony was written with a long slow movement, designed to be so soothing that the prince would surely fall asleep. On the evening of the performance, the prince did indeed drift off. Then, suddenly, a loud chord shattered the serenity of the murmuring movement. The prince awoke with a start and almost fell off his chair! Haydn adeptly gave the piece the name "Surprise Symphony."

On another occasion, Haydn was plagued by his musicians who were complaining that they were long overdue for vacations. He again faced the dilemma with ingenuity. Haydn composed a symphony during which the musicians' parts dropped off two by two. On the evening of the performance, Haydn saved this symphony as the last number, knowing that dusk would set in and the musicians would need to play the piece by candlelight. As each instrument's part finished, the musicians blew out their candles and left the stage until only Haydn was left. Prince Esterhazy got the message and sent everyone on vacation. Haydn named the piece "The Farewell Symphony."

When the prince for whom Haydn had served most of his career died, Haydn saw it as yet another opportunity. He packed his bags and traveled to London where he was employed by the entrepreneur J.P Salomon to compose symphonies. The demand for new music was incredible. Even at the age of sixty, Haydn's stamina was unquenchable and he produced perhaps his greatest work. Of these are the famous "London Symphonies."

After a return to Austria, Haydn turned to a new type of composition - the oratorio. He wrote "The Creation" and "The Seasons," both tributes to his love of nature and God. An enthusiastic hunter and fisherman and a man who considered his peace to come from God, it was not out of character for Haydn to turn to the topic, although the venture into a different music medium at such a late stage of his life might be considered unusual. Still, that was Haydn - never one to promote the usual.

Haydn died at the age of 77 on May 31, 1809. Elssler, Haydn's faithful servant, friend, and the chronicler of his works, wrote that Haydn passed from this world "quietly and peacefully," just as he had lived.

Haydn - a self-made man, remembered for his contribution to the symphony. But anecdotal studies of his life show he was also a man of optimism with an uncanny sense of humor. He was a mentor to other musicians and an untiring adventurer into almost every element of music.

http://www.essortment.com/all/franzjosephhay_rwml.htm

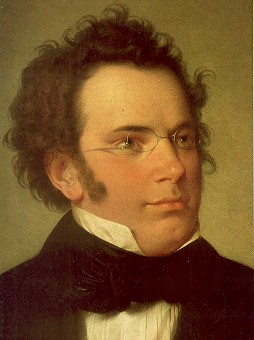

Franz Schubert

In some ways the work of Franz Schubert has always been overshadowed by the dominating presence of Beethoven. They were contemporaries in the same city of Vienna at the time of significant change in the development and shape of music. While Beethoven was comparatively well-known and well funded, and working towards a major revolution in musical expression, Schubert was younger, less well-known, under-funded and his innovations in musical expression were not so well recognised at the time. In many ways it was not until after his death that others started to recognise his genius. Some of his works were then published and performed for the first time, and gradually his talents became widely recognised. During his short lifetime the lack of widespread public awareness didn't seem to bother Schubert. His writings suggested a man who was driven to spend his time composing, and he relied instead on the feedback and support of a small circle of friends and admirers.

Franz Schubert belonged to a large family headed by his schoolmaster father. His father and a local teacher taught him music but his ability quickly exceed their standard. He joined the Imperial Court Chapel Choir as a boy soprano where he received further tuition, one of his teachers being the same Salieri who had been accused at one stage of poisoning Mozart (see the film "Amadeus" for more about this myth). When his voice broke he himself became a teacher and during this period he started to compose in earnest, eventually giving up teaching altogether so that he could devote even more time to his art. One of his brief teaching positions was to provide tuition to the daughters of Count Esterhazy in Hungary, for whose house Haydn had previously worked on a permanent basis. Physically Schubert was short and plump and short-sighted, and everything we know about him suggests that he was a quiet and private man. Although a skilled pianist and violinist, he was neither a virtuoso performer nor a flamboyant conductor who could promote his own work on the public stage. Many of his orchestra compositions were never performed publicly, and only his chamber music and songs were able to be performed in smaller social gatherings. The lack of significant publication and performance meant that his income was rather meagre.

Schubert was not completely devoid of supporters though. Over several years he gathered an intensely loyal group of associates who enjoyed his music and did what they could to support the young composer and promote his music. Firstly there was his brother who provided creative stimulation and possibly financial support. The baritone Johann Vogl grew very fond of Schubert's songs (of which he wrote some 600) and sang them on many occasions. In this way Schubert even managed to achieve a modest degree of success for his songs. This circle of friends included fellow musicians and socialites who attended get-togethers known as "Schubertiads" since they centred around the composer and his music. At times people helped to finance publication of some of his works and in this way, word of the composer did begin to spread. Schubert was a great admirer of Beethoven and is known to have visited him. When the great composer died, Schubert was a torch-bearer at his funeral. Unfortunately ill-health was to strike Schubert cruelly and he was soon to be buried very close to Beethoven. The younger composer had contacted Syphilis at one stage which was epidemic at the time, and just as he was beginning to take his music in new directions and achieve some modest recognition, he died of Typhoid Fever at the age of 31.

Schubert's music doesn't seem to be particularly influenced by Beethoven. Instead his style seems closer to the works of Haydn and Mozart. He was a prolific composer who sometimes even composed several songs per day. In all he completed more than 600 songs, and all of his music seems to be characterised by a certain tuneful lyricism. This could be lively and happy, or it could carry a certain wistfulness bordering on sadness. His songs are also notable for the strength of their piano accompaniment, which acts as an equal partner in the compositions, supporting the mood of the song with inventive phrases. Schubert's music also demonstrates certain novel techniques such as the juxtaposition of unusual chords and an ability to seemingly modulate with ease into any remote key. His symphonies were largely unknown to the general public in his lifetime, though they are now standards of the repertoire. The complete cycle depicts a growth in style and technique from the earlier Haydnesque ones up to the "Unfinished" 8th and the "Great" 9th. It may be that the 8th symphony was indeed finished and the final two movements have been lost. That has not diminished its standing in the music world, and those remaining two great movements demonstrate a unique talent for conveying emotion. Schubert also left a remarkable legacy of Chamber music, including several powerful String Quartets and Piano Sonatas. With some help from his brother, Schubert's works were later discovered by Schumann and Mendelssohn who were instrumental in their achieving a wider recognition. Some of the symphonies were similarly discovered much later by George Grove and Arthur Sullivan.

http://www.mfiles.co.uk/composers/Franz-Schubert.htm

Saturday, June 5, 2010

Robert Schumann

Robert Schumann was born 8 June, 1810 in Zwickau, Germany. He was the son of a book publisher and writer. As a child, Robert Schumann showed early abilities in both music and literature, but was not considered a prodigy by any means. At sixteen, after the tragic deaths of his sister and father, he was sent to the University of Leipzig at his mother's insistence. He studied law there until he was able to convince his mother of his need to study music.

In Leipzig, from 1830, he worked under the renowned piano teacher Friedrich Wieck, whose favourite daughter, Clara, was already a well-known piano prodigy. It is thought that Schumann and Clara were lovers by 1835. His own ambitions as a pianist were hampered by a weakness in the fingers of one hand (possibly caused by they syphilis that would later claim his sanity), but the 1830s nevertheless brought a number of marvellous compositions for the instrument.

Robert Schumann's work is noted for its links to literature. Many of his compositions allude to characters or scenes from poems, novels, and plays; others are like musical crossword puzzles with key signatures or musical themes that refer to people or places important to him. This intimate relationship with the written word gives his music an extra dimension. At the same time, its sheer joyfulness ranks it among the best loved music of the age.

Schumann was not only interested in literature, he was also a working journalist who edited his own influential musical magazine, the Neue Zeitsfchrift fur Musik. This put Schumann in a unique position: his music was often inspired by the world of words, while his work as writer and critic kept him in touch with the Romantic musical scene at large. Through his music journal he helped to bring the young Chopin and, later, the young Brahms to the attention of the German-speaking public.

Schumann's courtship of and marriage to Clara Wieck is one of the most famous romances in music history. Clara's father was one of Schumann's piano teachers. He predicted a great future for his pupil, but he fiercely opposed the young man's request to marry his daughter. He not only disapproved of Schumann's drinking, he also wanted Clara to become a famous pianist in her own right. For years Friedrich did everything he could to keep Schumann and Clara apart. Schumann eventually took Wieck to court and obtained permission to marry her, but it had been a long and bitter struggle.

Overall, Robert Schumann's early piano compositions, many of which were played by his wife Clara, are the most original and daring of his works. As a composer, he tended to concentrate on one type of music at a time. For instance, his songs qualify him as a worthy successor to Schubert. And while his great orchestral works remain closer to the traditional Classical forms of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, he is regarded as a talented, but not masterful. Nor was he successful as a composer of operas. It is in his piano music and his songs - Carnival ("Dainty Scenes on Four Notes") in particular - that he accomplished his greatest work.

In 1850 Schumann was appointed Music Director to the city of Dusseldorf, where he enjoyed no great success. Suffering from hallucinations and rapidly declining mental facilities, he resigned in 1853. Mounting fears of insanity plunged Schumann into a serious mental break-down, and in 1854 he attempted suicide by throwing himself into the Rhine. He was then confined to an asylum at Endenich, where he remained until his death on 29 July, 1856.

Frédéric François Chopin

Frédéric François Chopin was born in Zelazowa Wola (near Warsaw, Poland) on March 1, 1810 (or on February 22, according to his baptismal certificate). He was born into a small family of a French father, Nicolas Chopin, and of a Polish mother, Tekla Justyna Krzyzanowska. He showed great admiration for the piano at a very young age, and he composed two polonaises (Polish dances) at the age of seven years. At the same time, he gave concert performances to impressed audiences and, being humble, stated that the public was admiring the collar of his shirt.

He began his studies with violinist Wojciech Zywny in 1816. As he soon acquired greater skill than that of his teacher, he continued his studies at the Warsaw Conservatory, under the tutelage of Wilhelm Wurfel. At the age of 15 years, he published his first work (Rondo, op. 1). At 16, he began to study harmony, theory, figured bass and composition with Jozef Elsner, a Silesian composer who taught at the Conservatory.

In early 1829, Chopin performed in Vienna, where he was received with several optimistic reviews. The next year, he returned to his homeland and performed the premiere of his piano concerto in F minor, at the National Theatre on March 17. After these travels, Chopin decided to move to Paris, in order to eschew the volatile political situation back home. On the road, he learned that the Russians had captured Warsaw, and he composed the great “Revolutionary Etude,” in reaction thereto. Once in Paris, he began working on his first ballade (Op. 23) and scherzo (Op. 20), as well as his first etudes (Op. 10). It is also at this time that he began his unfortunate struggle with Tuberculosis.

In France, Chopin had the opportunity to acquaint himself with his contemporaries who were also participants of the Romantic Revolution in Paris. Among them were Liszt, Berlioz, Meyerbeer, Bellini, Balzac, Heine, Victor Hugo and Schumann. Reluctantly, the introvert expanded his horizons and made many lasting friendships. He also came across the friend of Liszt’s mistress, the French author best known by her pseudonym, George Sand. When they met, she was 34 and he was 28. Madame Sand was courageous and domineering: her need to dominate found its counterpart in Chopin’s need to be led. She left a memorable description of the composer at work:

His creative work was spontaneous, miraculous. It came to him without effort or warning... But then began the most heartrending labour I have ever witnessed. It was a series of attempts, of fits of irresolution and impatience to recover certain details. He would shut himself in his room for days, pacing up and down, breaking his pens, repeating and modifying one bar a hundred times.

The 1830s in Paris proved to be a progressive and productive time for Chopin. He completed some of his most popular works and performed regular concerts, receiving fantastic reviews. However, Chopin was not in favour of public performance; he therefore imposed a constant demand of himself as a composer and as a teacher. He was demanded in the Parisian salons, and he played less reluctantly under these circumstances.

Madame Sand shared the gelid winter of 1838-9 with Chopin. They stayed in an unheated peasant hut and in the Valldemossa Monastery. Chopin encountered many difficulties in acquiring a piano from Paris in these parts. Much of this miserable and desperate time is depicted in his 24 preludes (Op. 28), which were composed during this time. Due to the terrible conditions—and Chopin’s unpleasant reaction thereto—he and Madame Sand returned to Paris.

During the following eight years, Chopin spent his summers at Sand’s estate in Nohant. It is in this location that she entertained some of France’s most prominent artists and writers. Unfortunately, the couple’s happiness was relatively short-lived, and they shifted from love to conflict. Their intense relationship ended two years before Chopin’s death, in 1847. Sand had begun to suspect that Chopin had fallen in love with her daughter, Solange; they parted in rancour. One of Chopin’s best friends, Franz Liszt, stated that Chopin once declared that, in ending this long affection, he had ruined his life. Once found in his later letters: “What has become of my art? And my heart, where have I wasted it?”

On an interesting personal note, Chopin once stated that he had never been attracted to Sand. “Something about her repels me,” said he to his family. Moreover, Sand once suggested in her correspondence that Chopin was asexual; that is, he had no inclination to have sexual relations with anyone, male or female.

On October 17, 1849, tuberculosis ended the life of a young genius. At the age of 39, Chopin passed away, blessing us with no further melodies or harmonies. Thousands joined together to attend his funeral and to pay him homage. His funeral was held at the Church of the Madeleine, and he was buried at the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. His heart was entombed at the Church of the Holy Cross in Poland, and Polish soil was sprinkled over his tomb in France, as he had requested.

Every year, many inspired tourists visit Chopin’s grave to pay their respects. To this date, his music has been performed and recorded very frequently. The Composer of Poland is known as one of the best composers of the Romantic period; ironically, he did not consider himself of this group. He was the Poet of the Piano, and the intense expression and emotion present in his music is the cause of this common belief. Anyhow, his music has fuelled the inspiration of millions of musicians and will certainly continue to do so for quite some time.

http://www.chopinmusic.net/biographies/chopin/

Johann Sebastian Bach

( Eisenach, 21 March 1685; d Leipzig, 28 July 1750). German composer and organist [24 in Bach family genealogy]. He was the youngest son of Johann Ambrosius Bach, a town musician, from whom he probably learnt the violin and the rudiments of musical theory. When he was ten he was orphaned and went to live with his elder brother Johann Christoph, organist at St Michael's Church, Ohrdruf, who gave him lessons in keyboard playing. From 1700 to 1702 he attended St Michael's School in Lüneburg, where he sang in the church choir and probably came into contact with the organist and composer Georg Böhm. He also visited Hamburg to hear J. A. Reincken at the organ of St Catherine's Church.

After competing unsuccessfully for an organist's post in Sangerhausen in 1702, Bach spent the spring and summer of 1703 as ‘lackey’ and violinist at the court of Weimar and then took up the post of organist at the Neukirche in Arnstadt. In June 1707 he moved to St Blasius, Mühlhausen, and four months later married his cousin Maria Barbara Bach in nearby Domheim. Bach was appointed organist and chamber musician to the Duke of Saxe-Weimar in 1708, and in the next nine years he became known as a leading organist and composed many of his finest works for the instrument. During this time he fathered seven children, including Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel. When, in 1717, Bach was appointed Kapellmeister at Cöthen he was at first refused permission to leave Weimar and was allowed to do so only after being held prisoner by the duke for almost a month.

Bach's new employer, Prince Leopold, was a talented musician who loved and understood the art. Since the court was Calvinist, Bach had no chapel duties and instead concentrated on instrumental composition. From this period date his violin concertos and the six Brandenburg Concertos, as well as numerous sonatas, suites and keyboard works, including several (e.g. the Inventions and Book I of the ‘48’) intended for instruction. In 1720 Maria Barbara died while Bach was visiting Karlsbad with the prince; in December of the following year Bach married Anna Magdalena Wilcke, daughter of a court trumpeter at Weissenfels. A week later Prince Leopold also married, and his bride's lack of interest in the arts led to a decline in the support given to music at the Cöthen court. In 1722 Bach entered his candidature for the prestigious post of Director musices at Leipzig and Kantor of the Thomasschule there. In April 1723 after the preferred candidates, Telemann and Graupner, had withdrawn, he was offered the post and accepted it.

Bach remained as Thomaskantor in Leipzig for the rest of his life, often in conflict with the authorities, but a happy family man and a proud and caring parent. His duties centred on the Sunday and feastday services at the city's two main churches, and during his early years in Leipzig he composed prodigious quantities of church music, including four or five cantata cycles, the Magnificat and the St John and St Matthew Passions. He was by this time renowned as a virtuoso organist and in constant demand as a teacher and an expert in organ construction and design. His fame as a composer gradually spread more widely when, from 1726 onwards, he began to bring out published editions of some of his keyboard and organ music.

From about 1729 Bach's interest in composing church music sharply declined, and most of his sacred works after that date including the B minor Mass and the Christmas Oratorio consist mainly of ‘parodies’ or arrangements of earlier music. At the same time he took over the direction of the collegium musicum that Telemann had founded in Leipzig in 1702 - a mainly amateur society which gave regular public concerts. For these Bach arranged harpsichord concertos and composed several large-scale cantatas, or serenatas, to impress the Elector of Saxony, by whom he was granted the courtesy title of Hofcompositeur in 1736.

Among the 13 children born to Anna Magdalena at Leipzig was Bach's youngest son, Johann Christian, in 1735. In 1744 Bach's second son, Emanuel, was married and three years later Bach visited the couple and their son (his first grandchild) at Potsdam, where Emanuel was employed as harpsichordist by Frederick the Great. At Potsdam Bach improvised on a theme given to him by the king, and this led to the composition of the Musical Offering, a compendium of fugue, canon and sonata based on the royal theme. Contrapuntal artifice predominates in the work of Bach's last decade, during which his membership (from 1747) of Lorenz Mizler's learned Society of Musical Sciences profoundly affected his musical thinking. The Canonic Variations for organ was one of the works Bach presented to the society, and the unfinished Art of Fugue may also have been intended for distribution among its members.

Bach's eyesight began to deteriorate during his last year, and in March and April 1750 he was twice operated on by the itinerant English oculist John Taylor. The operations and the treatment that followed them may have hastened Bach's death. He took final communion on 22 July and died six days later. On 31 July he was buried at St John's cemetery. His widow survived him for ten years, dying in poverty in 1760.

Bach's output embraces practically every musical genre of his time except for the dramatic ones of opera and oratorio (his three ‘oratorios’ being oratorios only in a special sense). He opened up new dimensions in virtually every department of creative work to which he turned, in format, musical quality and technical demands. As was normal at the time, his creative production was mostly bound up with the external factors of his places of work and his employers, but the density and complexity of his music are such that analysts and commentators have uncovered in it layers of religious and numerological significance rarely to be found in the music of other composers. Many of his contemporaries, notably the critic J. A. Scheibe, found his music too involved and lacking in immediate melodic appeal, but his chorale harmonizations and fugal works were soon adopted as models for new generations of musicians. The course of Bach's musical development was undeflected (though not entirely uninfluenced) by the changes in musical style taking place around him. Together with his great contemporary Handel (whom chance prevented his ever meeting), Bach was the last great representative of the Baroque era in an age which was already rejecting the Baroque aesthetic in favour of a new, ‘enlightened’ one.

http://www.answers.com/topic/johann-sebastian-bach

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (German: [ˈvɔlfɡaŋ amaˈdeus ˈmoːtsaʁt], full baptismal name Johannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart (27 January 1756 – 5 December 1791), was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical era. He composed over 600 works, many acknowledged as pinnacles of symphonic, concertante, chamber, piano, operatic, and choral music. He is among the most enduringly popular of classical composers.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (German: [ˈvɔlfɡaŋ amaˈdeus ˈmoːtsaʁt], full baptismal name Johannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart (27 January 1756 – 5 December 1791), was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical era. He composed over 600 works, many acknowledged as pinnacles of symphonic, concertante, chamber, piano, operatic, and choral music. He is among the most enduringly popular of classical composers.Mozart showed prodigious ability from his earliest childhood in Salzburg. Already competent on keyboard and violin, he composed from the age of five and performed before European royalty; at 17 he was engaged as a court musician in Salzburg, but grew restless and traveled in search of a better position, always composing abundantly. While visiting Vienna in 1781, he was dismissed from his Salzburg position. He chose to stay in the capital, where he achieved fame but little financial security. During his final years in Vienna, he composed many of his best-known symphonies, concertos, and operas, and the Requiem. The circumstances of his early death have been much mythologized. He was survived by his wife Constanze and two sons.

Mozart learned voraciously from others, and developed a brilliance and maturity of style that encompassed the light and graceful along with the dark and passionate—the whole informed by a vision of humanity "redeemed through art, forgiven, and reconciled with nature and the absolute." His influence on subsequent Western art music is profound. Beethoven wrote his own early compositions in the shadow of Mozart, of whom Joseph Haydn wrote that "posterity will not see such a talent again in 100 years."

Mozart fell ill while in Prague for the premiere on 6 September of his opera La clemenza di Tito, written in 1791 on commission for the Emperor's coronation festivities. He was able to continue his professional functions for some time, and conducted the premiere of The Magic Flute on 30 September. The illness intensified on 20 November, at which point Mozart became bedridden, suffering from swelling, pain, and vomiting.

Mozart was nursed in his final illness by Constanze and her youngest sister Sophie, and attended by the family doctor, Thomas Franz Closset. It is clear that he was mentally occupied with the task of finishing his Requiem. However, the evidence that he actually dictated passages to his student Süssmayr is very slim.

Mozart died at 1 a.m. on 5 December 1791 at the age of 35. The New Grove gives a matter-of-fact description of his funeral:

Mozart was buried in a common grave, in accordance with contemporary Viennese custom, at the St Marx cemetery outside the city on 7 December. If, as later reports say, no mourners attended, that too is consistent with Viennese burial customs at the time; later Jahn (1856) wrote that Salieri, Süssmayr, van Swieten and two other musicians were present. The tale of a storm and snow is false; the day was calm and mild.

The cause of Mozart's death cannot be known with certainty. The official record has it as "hitziges Frieselfieber" ("severe miliary fever", referring to a rash that looks like millet seeds), a description that does not suffice to identify the cause as it would be diagnosed in modern medicine. Dozens of theories have been proposed, including trichinosis, influenza, mercury poisoning, and a rare kidney ailment. The most widely accepted hypothesis is that Mozart died of acute rheumatic fever. For further discussion, see Death of Mozart.

Mozart's sparse funeral did not reflect his standing with the public as a composer: memorial services and concerts in Vienna and Prague were well attended. Indeed, in the period immediately after his death Mozart's reputation rose substantially: Solomon describes an "unprecedented wave of enthusiasm"[66] for his work; biographies were written (first by Schlichtegroll, Niemetschek, and Nissen; see Biographies of Mozart); and publishers vied to produce complete editions of his works.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wolfgang_Amadeus_Mozart

Ludwig van Beethoven

(Bonn, bap. 17 Dec 1770; d Vienna, 26 March 1827). German composer. He studied first with his father, Johann, a singer and instrumentalist in the service of the Elector of Cologne at Bonn, but mainly with C. G. Neefe, court organist. At 11½ he was able to deputize for Neefe; at 12 he had some music published. In 1787 he went to Vienna, but quickly returned on hearing that his mother was dying. Five years later he went back to Vienna, where he settled.

He pursued his studies, first with Haydn, but there was some clash of temperaments and Beethoven studied too with Schenk, Albrechtsberger and Salieri. Until 1794 he was supported by the Elector at Bonn: but he found patrons among the music-loving Viennese aristocracy and soon enjoyed success as a piano virtuoso, playing at private houses or palaces rather than in public. His public début was in 1795; about the same time his first important publications appeared, three piano trios op.1 and three piano sonatas op.2. As a pianist, it was reported, he had fire, brilliance and fantasy as well as depth of feeling. It is naturally in the piano sonatas, writing for his own instrument, that he is at his most original in this period; the Pathétique belongs to1799, the Moonlight (‘Sonata quasi una fantasia’) to1801, and these represent only the most obvious innovations in style and emotional content. These years also saw the composition of his first three piano concertos, his first two symphonies and a set of six string quartets op.18.

1802, however, was a year of crisis for Beethoven, with his realization that the impaired hearing he had noticed for some time was incurable and sure to worsen. That autumn, at a village outside Vienna, Heiligenstadt, he wrote a will-like document, addressed to his two brothers, describing his bitter unhappiness over his affliction in terms suggesting that he thought death was near. But he came through with his determination strengthened and entered a new creative phase, generally called his ‘middle period’. It is characterized by a heroic tone, evident in the ‘Eroica’ Symphony (no.3, originally to have been dedicated not to a noble patron but to Napoleon), in Symphony no.5, where the sombre mood of the C minor first movement (‘Fate knocking on the door’) ultimately yields to a triumphant C major finale with piccolo, trombones and percussion added to the orchestra, and in his opera Fidelio. Here the heroic theme is made explicit by the story, in which (in the post-French Revolution ‘rescue opera’ tradition) a wife saves her imprisoned husband from murder at the hands of his oppressive political enemy. The three string quartets of this period, op.59, are similarly heroic in scale: the first, lasting some 45 minutes, is conceived with great breadth, and it too embodies a sense of triumph as the intense F minor Adagio gives way to a jubilant finale in the major, embodying (at the request of the dedicatee, Count Razumovsky) a Russian folk melody.

Fidelio, unsuccessful at its première, was twice revised by Beethoven and his librettists and successful in its final version of 1814. Here there is more emphasis on the moral force of the story. It deals not only with freedom and justice, and heroism, but also with married love, and in the character of the heroine Leonore, Beethoven's lofty, idealized image of womanhood is to be seen. He did not find it in real life: he fell in love several times, usually with aristocratic pupils (some of them married), and each time was either rejected or saw that the woman did not match his ideals. In 1812, however, he wrote a passionate love-letter to an ‘Eternally Beloved’ (probably Antonie Brentano, a Viennese married to a Frankfurt businessman), but probably the letter was never sent.

With his powerful and expansive middle-period works, which include the Pastoral Symphony (no.6, conjuring up his feelings about the countryside, which he loved), Symphonies nos.7 and 8, Piano Concertos nos.4 (a lyrical work) and 5 (the noble and brilliant ‘Emperor’) and the Violin Concerto, as well as more chamber works and piano sonatas (such as the ‘Waldstein’ and the ‘Appassionata’) Beethoven was firmly established as the greatest composer of his time. His piano-playing career had finished in 1808 (a charity appearance in 1814 was a disaster because of his deafness). That year he had considered leaving Vienna for a secure post in Germany, but three Viennese noblemen had banded together to provide him with a steady income and he remained there, although the plan foundered in the ensuing Napoleonic wars in which his patrons suffered and the value of Austrian money declined.

The years after 1812 were relatively unproductive. He seems to have been seriously depressed, by his deafness and the resulting isolation, by the failure of his marital hopes and (from 1815) by anxieties over the custodianship of the son of his late brother, which involved him in legal actions. But he came out of these trials to write his profoundest music, which surely reflects something of what he had been through. There are seven piano sonatas in this, his ‘late period’, including the turbulent ‘Hammerklavier’ op.106, with its dynamic writing and its harsh, rebarbative fugue, and op.110, which also has fugues and much eccentric writing at the instrument's extremes of compass; there is a great Mass and a Choral Symphony, no.9 in D minor, where the extended variation-finale is a setting for soloists and chorus of Schiller's Ode to Joy; and there is a group of string quartets, music on a new plane of spiritual depth, with their exalted ideas, abrupt contrasts and emotional intensity. The traditional four-movement scheme and conventional forms are discarded in favour of designs of six or seven movements, some fugal, some akin to variations (these forms especially attracted him in his late years), some song-like, some martial, one even like a chorale prelude. For Beethoven, the act of composition had always been a struggle, as the tortuous scrawls of his sketchbooks show; in these late works the sense of agonizing effort is a part of the music.

Musical taste in Vienna had changed during the first decades of the 19th century; the public were chiefly interested in light Italian opera (especially Rossini) and easygoing chamber music and songs, to suit the prevalent bourgeois taste. Yet the Viennese were conscious of Beethoven's greatness: they applauded the Choral Symphony, even though, understandably, they found it difficult, and though baffled by the late quartets they sensed their extraordinary visionary qualities. His reputation went far beyond Vienna: the late Mass was first heard in St Petersburg, and the initial commission that produced the Choral Symphony had come from the Philharmonic Society of London. When, early in 1827, he died, 10 000 are said to have attended the funeral. He had become a public figure, as no composer had done before. Unlike composers of the preceding generation, he had never been a purveyor of music to the nobility: he had lived into the age - indeed helped create it - of the artist as hero.

http://www.answers.com/topic/ludwig-van-beethoven

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)